History of Cartomancy and Tarot

The Origins of Playing Cards

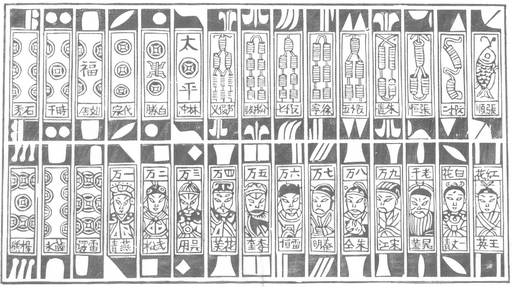

Research indicates that cards made from paper most likely originated in China, possibly as early as the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) when woodblock printing was invented, and that they were used for playing games and gambling. They may also have functioned in China as a form of paper currency.

By the middle of the 15th Century CE, play-money cards divided into four suits were reported in China. The suit designs derived from those on early Chinese banknotes and each suit had a different value. Many scholars believe that these Chinese money cards inspired the familiar four-suited pip cards of Western playing cards.

The earliest playing cards considered to have directly influenced later Western designs are the so-called Mamluk cards, named after the Islamic Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517 CE) when they are presumed to have been made. These have elaborate hand-painted patterns very similar to those found on Chinese money cards and, like money cards, are divided into four suits. It has been claimed that a few apparent Mamluk card fragments may date from the 13th or 14th centuries, but the two surviving (though incomplete) decks have been dated to the 15th century.

From Left: 6 of Coins, 4 of Polo Sticks, 3 of Cups, 7 of Swords

The complete Mamluk decks would have contained 52 (possibly 56) cards, comprised of four suits of 13 (possibly 14) cards. The suits are:

- SWORDS (or SCIMITARS)

- POLO STICKS

- CUPS

- COINS

Each suit has ten pip cards and three court cards with Arabic inscriptions that can be translated as king, viceroy (or governor), and second governor. There is also a possible fourth court card that indicates a helper or aide, although this may be an alternate representation of the king. Interestingly, these inscriptions suggest that the court cards may have had some oracular meaning. For example, the inscription for the helper of coins has been translated as, 'Rejoice in the happiness that returns as a bird sings its joy' (Kaplan, 1978, p.53).

By the late 14th or early 15th century, these 'Moorish' cards had entered Europe, most likely overland to Italy via Turkey, and by sea via the Iberian peninsula. Their designs were reproduced in Italy, Spain and other European countries, but simplified and adapted for the local markets. In this way, polo sticks (unknown in Europe) became clubs and the court cards changed to King, Queen, and Knave. The suit designs also became increasingly stylized, although with national and regional differences. Eventually, the 'French' style of suit designs became dominant in the English-speaking world - swords were changed to spades, cups to hearts, coins to diamonds, and clubs were represented by a three-leaf clover. The French style also standardized the deck at 52 cards, with four suits of 13 cards.

In the United States during the 1850s, a Joker was added to the deck as a trump card in the popular game of Euchre. Since that time, these standard French-suited decks have generally included one or two jokers for use as a special trump or wild card in various games.

The Invention of Tarot

Although it is sometimes claimed that tarot cards date back more than a thousand years - perhaps to Ancient Egypt or to early migrations of Romany people from India - modern scholarship suggests that the tarot most likely originated in Italy or Germany sometime in the 15th century CE.

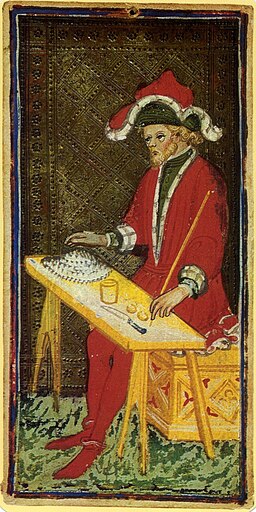

From the Pierpont Morgan-Bergamo tarocchi deck

In Italy, the cards were known as Trionfi (Triumphs, or Trumps) and were used for playing a game of the same name. By the early 16th century, a similar game known as Tarocho (later tarocchi or tarocchini) became popular, from which the modern word Tarot is derived.

Cards from several early tarot decks have beautiful hand-painted illuminations and were therefore expensive to produce. Among these, the several 15th century Visconti-Sforza Tarot sets are exquisite. In addition to their use in games, these may also have served as status symbols to be cherished and displayed by the wealthy Italian families who commissioned them. The allegorical imagery that characterizes many of the cards also suggests that they may have had an educational purpose.

Although no complete Visconti-Sforza tarocchi decks have survived, the most complete set is 74 cards from the Pierpont Morgan-Bergamo deck. Originally, this deck comprised 78 untitled cards - 22 unnumbered trump cards and four 14-card suits, representing Batons, Cups, Swords, and Coins. Because there are no words on the cards, the original titles of the four court cards remain unclear. Also, other surviving examples of Visconti-Sforza tarocchi cards exhibit variations suggesting that the 78-card composition of these decks was not universally accepted at this time.

The trumps and suited cards have formed one deck for many centuries. It is likely, however, that they were originally two separate sets, each used for a different game, and were combined into a gaming deck of 78 cards (along with other variants) sometime in the 15th century.

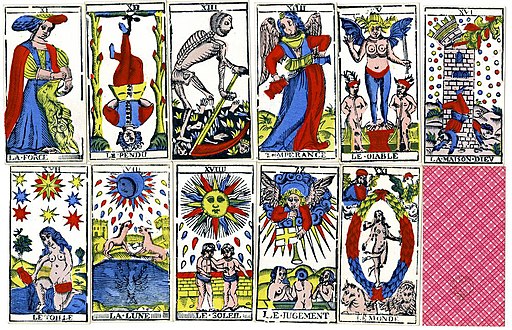

By the mid 18th century, the Italian game had spread into France and other European countries due to the popularity of the printed Tarot de Marseilles, which was first produced in the mid 17th century.

(Modern reproduction)

Despite the earlier variations in the composition of tarocchi sets, The Tarot de Marseilles helped to establish the now familiar 78-card tarot deck of 22 named Trump cards (21 numbered cards and an unnumbered Fool) and four 14-card suits.

Unlike playing cards, where the suit designations and patterns changed and became stylized over time, most tarot decks have retained the traditional Marseilles attributions in which the suits are Batons, Cups, Swords, and Coins. The four court cards also typically continue to be based on the names used in the Marseilles deck - King, Queen, Knight, and Knave or Page.

The Esoteric Tarot

In the late 18th century, the Tarot de Marseilles came to the attention of the Protestant Pastor and Freemason, Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725-1784). De Gébelin interpreted the tarot as encapsulating the wisdom of the Book of Thoth of the ancient Egyptians. He also promoted a presumed connection between the 22 tarot trumps and the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

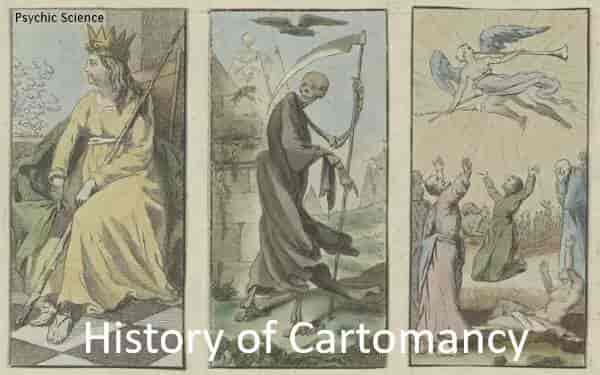

Shortly after the publication of de Gébelin's theories, Jean-Baptiste Alliette (1738–1791), writing under the pseudonym Etteilla, released the first systematic guide to esoteric tarot reading. Etteilla was also the first to connect the four card suits to the four classical elements (Fire, Earth, Air, and Water) and to propose correspondences between tarot cards and astrological principles including the planets and zodiac signs. As a result of his deliberations, Etteilla created and published his own original tarot deck (Livre de Thot), specially designed for use in divination, and developed various consultation procedures, or 'spreads'.

The Queen of France (#23), Death (#17), The Last Judgement (#16)

Public Domain (Wellcome Collection)

Through the work of de Gébelin and Etteilla, the tarot attracted the interest of many occultists, Kabbalists, and other esoteric practitioners, especially those following the Western magical tradition. Notable among these are Alphonse Louis Constant [Éliphas Lévi] (1810–1875), Jean-Baptiste Pitois [Paul Christian] (1811-1877), A.E. Waite (1857–1942), Gérard Encausse [Papus] (1865–1916), and Aleister Crowley (1875-1947).

In esoteric traditions, the 22 trumps are generally known as the 'Major Arcana' and the 56 suited cards as the 'Minor Arcana', terms that were first used in 1870 by Jean-Baptiste Pitois, writing under the pseudonym Paul Christian. Although nowadays the Major Arcana are usually considered to be the most significant divinatory indicators, early records suggest that it was the regular suited cards that were first used for fortune-telling. For example, the Mainzer Kartenlosbuch (Mainz Fortune-Telling Book), believed to have been published around 1487, gives oracular meanings to the suited cards, whereas no documents have been found to show that the tarocchi (trump) cards were used for fortune-telling in the 15th century (Kaplan, 1978).

In the late 19th century, tarot divination also became an important element in the curriculum of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. A.E. Waite and Aleister Crowley (both former members of the Golden Dawn) each created their own versions of the tarot in collaboration, respectively, with occultists and artists Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951) and Lady Frieda Harris (1877-1962). Waite's popular Rider-Waite Tarot was first published in 1909 and Aleister Crowley's distinctive Thoth Tarot designs were first illustrated in 'The Book of Thoth' (1944), although the cards themselves remained unpublished for many years.

The Modern Tarot Revival

The modern fascination with spirituality, mysticism, psychism, and the occult began in the 1960s and led to a revival of interest in systems of divination such as the I Ching and tarot. At that time, tarot decks were hard to find and often expensive. However, in 1969, the Crowley-Harris Thoth Tarot deck was finally issued by US publishers Llewellyn. In 1971, US Games Systems acquired the rights to publish the Rider-Waite Tarot although the original Rider-Waite edition remains in the public domain. Also in the 1970s, the French card manufacturer Grimaud published a reproduction of the Tarot de Marseilles, and a modernized version of Etteilla's Livre de Thot called the Grand Etteilla.

The original Golden Dawn tarot cards had never been published but, in 1978, US Games Systems published an attempted reconstruction by Israel Regardie and Robert Wang as The Golden Dawn Tarot. Other reconstructed 'Golden Dawn' tarot decks have since been released, including The New Golden Dawn Ritual Tarot, designed by Chic and Tabatha Cicero (1991), and The Classic Golden Dawn Tarot by Pat Zalewski, Richard Dudschus, and David Sledzinski (2004/2022).

In recent years, tarot decks have become highly collectible and modern reproductions of several historical decks have been issued, together with new tarot designs based on a variety of interpretive approaches, including Jungian psychology, Buddhism, Wicca, Druidry, alchemy, and Arthurian legend. It has also become fashionable for artists and illustrators to design and publish decks containing their own original artwork. Although many of these artistic decks are very beautiful, only a few offer any new insights into the structure and meaning of the tarot, or the process of tarot divination.

Further Study

Websites

Origins of Cartomancy (Playing Card Divination)

Books

CAVENDISH, Richard (1975). The Tarot. Michael Joseph.

DECKER, Ronald, DEPAULIS, Thierry, & DUMMETT, Michael. (1996). A Wicked Pack of Cards: The Origins of the Occult Tarot. Duckworth.

DECKER, Ronald & DUMMETT, Michael. (2013). A History of the Occult Tarot. Duckworth.

GREER, Mary K. (2019). Tarot for Your Self: A Workbook for the Inward Journey. Weiser Books.

HARGRAVE, Catherine P. (2012). A History of Playing Cards and a Bibliography of Cards and Gaming. Dover Publications.

KAPLAN, Stuart R. (1978). The Encyclopedia of Tarot, Volume 1. U.S. Games Systems.